In this concert, Barber’s music explores universal undercurrents of American existence, while Copland’s convivial “Appalachian Spring” resonates with thoughtful simplicity – emanating from hard-won wisdom. This music hides the profound in the open. For, though we listen to these works, now so familiar and popular, we often forget to hear them – as I experienced in the following short story.

It was September 2006 and I had just started my new position as Resident-Conductor at the Juilliard School. The Juilliard Orchestra was asked to participate in an event at the New York Public Library commemorating the

Fifth Anniversary of the September 11, 2001 attacks. Juilliard President Joseph Polisi asked me to conduct Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings for the occasion. Certainly, a well-known piece appropriate for the setting, I had played it many times as a violinist, though never conducted it. While the gravity of the event was unquestionable, performing the Adagio was not a heavy concern. Then, I opened the score.

The simple printed notes concealed the profundity evoked by their incantation. Rather than guiding me, the music personally challenged me. Author Thomas Larson calls this work “America’s secular hymn for grieving the dead.” But it was more than merely sad. It was oddly sacred, ritual, and searching. A Twentieth-Century work, it alluded to ancient plainsong, – or older, a Kaddish. The score could even have come from the Liber Usualis, with its invocatio ns and responses. And though it had no text, it was intensely asking for an answer. But, what was the question?

I stared at those pages for hours … nothing. Finally, I decided to listen to it in a state of free association. Everything that came to mind, I wrote down – 9/11, cathedrals, synagogues, processions, rituals, caves, tombs, emotions. My mind became an endless chamber in which my own long-buried memories echoed unresolved. As I looked down at my scribbles, they loosely resembled a poem – each stanza the opening intonation; each responsory longer

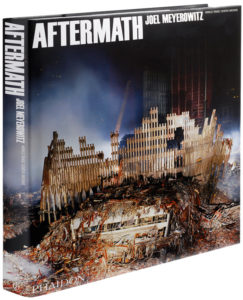

and more intense. I had found my journey within this music. After the performance, photographer Joel Meyerowitz exhibited photographs from “Aftermath,” his deeply moving book of images from 9/11’s Ground Zero. I could tell by the reactions to those photographs that the shared experience of this grievous event also had a deeper, unspoken meaning for each individual.

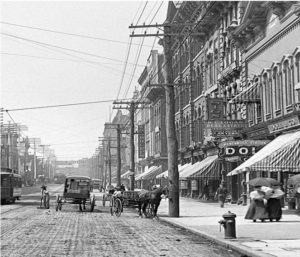

I hope you will accept Samuel Barber’s invitation to discover your own intimate narrative within his graspable, romantic music. The Adagio for Strings allows you a contemplative, private exploration of your memories – memories known only to you. The Capricorn Concerto offers a quirky juxtaposition of musical styles, counterpoint, and texture that one could associate with some of his contemporaries. His Knoxville Summer of 1915 captures the spirit of James Agee’s story about lost innocence and the desire for “the good old days.” With a dreamy, you-can’t-go-home-again quality, its haunting beauty brings us to our own place of nostalgia, longing, and empathy.